Gaspard-Félix Tournachon was born 200 years ago, on the 6th of April 1820. Who, you might ask. He is better known as Nadar, a photographer and so much else. Shelley Rice writes that he was one of the Second Empire’s quintessential “servants of illusion”. For me Nadar is the photographer of underground Paris, of catacombs and sewers, places that I have visited, too.

Nadar’s father died when Félix was eighteen years old and after that he “paid his own way as a journalist, a caricaturist, a political activist, a novelist, a photographer, a balloonist, and a prophet of aviation throughout his long life, which ended where it had begun, in Paris, in 1910”. That’s what Shelley Rice wrote about Félix Nadar in Parisian Views (1997).

He produced, as Rice writes, what is today regarded as one of the most important photographic records of Parisians during the Second Empire. He photographed writers, artists, actors, politicians and so on and they all were also his friends.

If you want to learn more about Nadar as portrait photographer, please check this article called ‘Félix Nadar: The world’s first celebrity photographer’. Even though Nadar knew “everyone”, he didn’t document the life of people in Paris. “Rather, Nadar chose projects that by definition excluded people”, writes Rice.

I am not going to write about Nadar as a portrait photographer, but Nadar as an underground photographer, photographing the sewers and catacombs. I got to know about Nadar because of those photographs. He was also photographing Paris from above, from a balloon. He was the first photographer ever taken pictures from balloon or with artificial light. Nadar applied for a patent for the system of lights and reflectors using Bunsen batteries and he got it patented in February 1861. You can read about the use of artificial light and his underground photography in the virtual galleries of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

(There are some great articles/websites about my subject, so I give links to them in the article or in the end.)

Félix Nadar began experimenting with photography by artificial light in 1859; he applied for a patent for it in 1861. Some one hundred photographs, first of the catacombs, in 1862, then of the sewers, in 1865, constitute the most spectacular application of his technique. These photographic essays actually concerned current events: the sanitizing of Paris imposed by the imperial authorities after the terrible cholera epidemics. (Source)

I have noticed that different writers give totally different years and timespans for the sewer work. I guess I try to trust to the above mentioned years as they come from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, who are having those photographs in their collections. And the year 1865 for sewer photos sounds correct as I have seen the same year mentioned elsewhere. (Rice gives year 1861 even though all the images that are used in the book are from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Also the same year is in Wikimedia Commons, so that’s why there is a year 1861 mentioned, if someone clicks to see the source of the photo.) According to Rice, Nadar visited first sewers and then catacombs, doing both visits in 1861. If any of my readers has a good knowledge about this, please let me know.

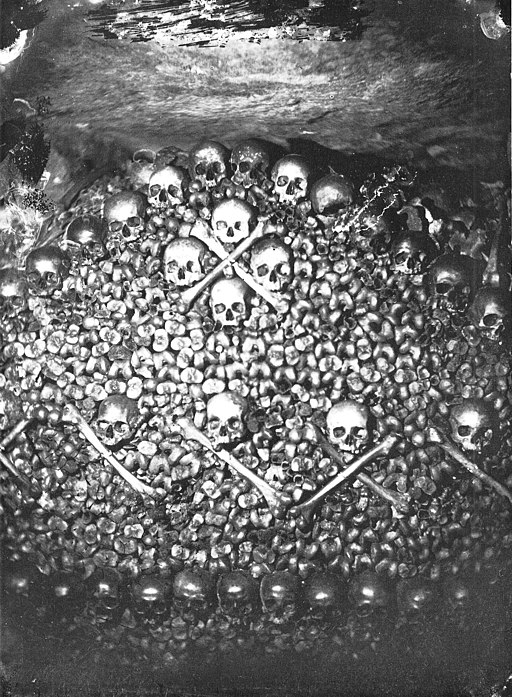

The catacombs

Nadar started his underground tasks in the catacombs in 1861. According to Christopher Prendergast Nadar’s “primary purpose appears to have been technical – to explore the possibilities of the patent he had recently taken out for the development of photography by means of electric light – and a great deal of his own account of the venture is concerned with the challenges and difficulties of the adverse conditions he encountered.” (Prendergast, p.82)

Shelley Rice saw Nadar also as a Romantic “in his fascination with death and debris, as well as in his compulsion to explore a landscape whose very function was to subsume all traces of individuality within a great nothingness” (Rice, p. 159). “Death, the great equalizer, writes Nadar, abolishes all distinctions of history, class, reputation, rich and poor, famous and anonymous…” (Prendergast, p. 81) Yes, Nadar was a Romantic.

Rice writes that a few of Nadar’s pictures suggest the weary melancholy of memento mori. Rice writes a bit more about a photo that I show below. It differs from the rest of the series as there is no heaps of bones or carefully assembled walls made of bones and skulls. “This nature morte is almost centered, and it is highlighted by Nadar’s artificial light”, writes Rice.

But such dramatic treatment only emphasizes the insignificance of these tiny human remains, detritus that seems to float in the void of darkness dominating the photograph. Most of the picture plane is empty space, so the formal construction of the image is defined not by objects but by the patterns of light and darkness that encircle the soil and stones of the cave. The light might illuminate a skull or reveal, on the left and in the background, a lettered sign or some other vestige of human life. But it is clear also that this light is transitory and weak, soon to be swallowed by the shadows. (Rice, p. 160)

But in Haussmann’s Paris, everything had to be in order. Nadar visited the catacombs when the work was in progress as the last bones deposits happened in the 1860s.

Many of the pictures shows the skulls and femurs in order, and neat, decorated walls, pathways, as well as the markers that tells the origin of various groups of bones.

Please check Public Domain Review’s wonderful article about Nadar’s catacombs photography. There you can see more photographs from this fascinating place.

The sewers

During the massive city transformation by Baron Haussmann also the Paris sewers were renewed. The new sewage system was not anymore the system described in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Rice writes that Hugo preferred the old days, when there was “mire, but soul” (as put in the book). And he started writing the book before the sewer renovation started. Hugo was talking about the old sewers, Nadar was photographing the new sewers.

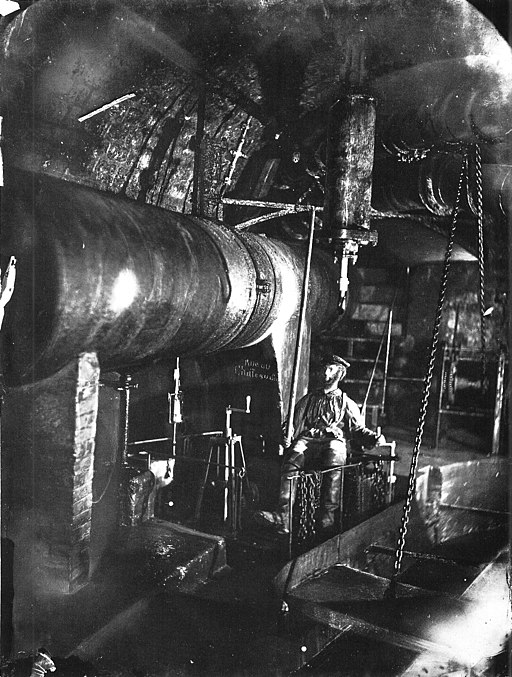

Nadar got the permission to work underground from Eugène Belgrand, the engineer who had been chosen by Haussmann to do the job. Nadar visited the sewers in the midst of the project. He saw and photographed clean galleries, crossroads, machinery and, like Rice writes, to his amazement and suspicion there were no signs of rats or poisons. (I don’t know about poisons, but that’s true, there are no rats, the only rat I have seen there – in the museum that is located in the sewers – was very dead one, washed there with a flood.) Rice continues: “All smelly vestiges of the past – like the stones of the city and the bones of its dead – had been laundered by the new, efficient underground system, geared toward the perpetual “circulation of mud”.” (Rice, p. 167)

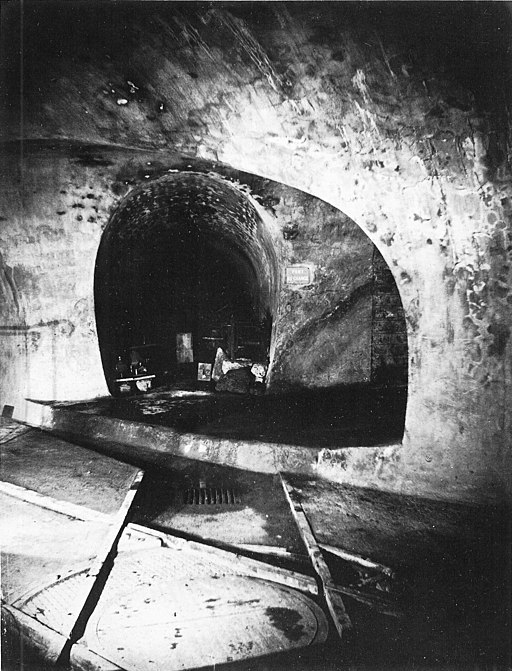

Nadar’s photos are documents of the underground world, and like David P. Jordan writes, “the sewers are presented as a world apart, cold, silent, austere, and peopled by another race, the sewer men in their uniforms and special boots”. And he continues, “the bowels of the city were now exposed and no longer mysterious or terrifying.” (Jordan, p. 277)

Shelley Rice writes about Nadar’s sewer images that the point of view in the images were chosen to express that above mentioned “circulation of mud”:

The images are most often constructed on the diagonal or in such a way that the sewer galleries plunge rapidly into deep space, giving the photographs a dynamism most often associated during those years with pictures of the new, wide boulevards [—] or the railroads [—]. His image of the galleries under the Pont au Change, for instance [see the image below], depicts the architectural arcade, almost centered in the picture, as it recedes into darkness. But this balanced composition is set in motion by the abstract forms that surround it – and that forge numerous connections between this picture and the Constructivist works of the first quarter of the twentieth century. The open-ended egg-shaped gallery encircling the arcade swings the image toward the left, a movement reiterated by horizontal tracks of the sluice cars. Since this is a crossroad, the tracks moving on the diagonal from right to left are intersected by others plunging back into deep space, their linear forms enlivened by the circles of the turntable between them and the stripes of a grill in the middle ground. (Rice, p. 167)

Jordan writes that the sewers were peopled by another race, the sewermen, except the sewermen in Nadar’s pictures were not real humans, but definitely “another race”: dummies. He used the flexible, versatile, and lifelike mannequins doing things that the workers in catacombs or in the sewers were doing in a real life. And why’s that: because he couldn’t ask anybody to pose for the necessary 18-minute exposure time (except himself for the self-portrait in the catacombs).

In theory, the use of dummies was designed to enhance the ‘natural’ realism of the photograph, to generate a certain ‘reality effect’. In fact, the dummies confer on the image a further atmosphere of theatrical unreality, and, as themselves ghostly presences, fake living beings engaged in stacking the fragmented remains of the dead, evoke one of the perspectives described by Nadar himself for the interpretation of the photographs – as a modern version of the traditional vanitas. (Prendergast, p. 81)

Conclusion

“ …, but the real fascination of these works lies in the sheer radicalism of the vision that conceived and executed them”, Shelley Rice writes. (p. 147) Walter Benjamin had written in Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century that “Nadar’s lead over his professional colleagues was demonstrated when he embarked on taking snapshots in the Paris sewers. Thus for the first time discoveries were required of the lens.”

Rice writes that Nadar used his camera to document that moment, the then-present, rather than to express his nostalgia or preservationist instincts. (p. 156) He documented things that were most characteristic of innovative urban planning of the time. That’s why he photographed the new Paris from above and sewers under the surface. Nadar had loved the old Paris, but he didn’t show that in his pictures.

“[O]ne might say that the true significance of Nadar’s photographs is that they record, and celebrate, the encounter of two technologies, the progress of his own demonstrated in its capacity to record progress in the other.” (Prendergast, p.82)

Nevertheless, Prendergast is not seeing Nadar’s photographs solely as documents, but he goes deeper into them in his book Paris and the Nineteenth Century; or into the ideas of what sewers or catacombs with the piled bones are representing – compared with the overground society:

… whatever their deliberate or unintended ironies, Nadar’s photographs finally present a view of Paris underground that must have been largely congenial to the official view. The principal connotation of the visual denotations is one of efficient mastery of the problem of disposing of bodily detritus. If the skeletal fragments sometimes look as if they are threatening to overwhelm the capacity of the ‘system’ to organize them, the dominant image is of rows of skulls and bones arranged in neat and tidy patterns; although individual ‘identity’ has been obliterated in the random anonymity of the pile, the pile itself has the identity of ordered space, clean, coherent and cost-efficient, testimony to the victory of technological modernity over a proliferating disorder. (Prendergast, p. 81)

Prendergast notes that this “implication of order triumphant is even stronger in the photographs of the modernized sewers”.

Rice writes that even though the subject of the three documentary series (these two I have covered here plus the series taken from above, from a balloon) differ widely, the underlying structures of the photographs in the series are very much related, because the new urban order was everywhere. As she notes in her book, in the nineteenth century Paris also waste and corpses must be subject to order and control. All these images of Paris are about dynamism, circulation, change, and, as a result, about a new, thoroughly modern kind of death. (Rice, p. 177)

Nadar was photographing that order even though he longed for Paris that didn’t exist anymore. He was looking for the heart of the city, but he didn’t find it, there was

no heart, no eternal truth left, that it too had been demolished and rebuilt in this metropolis where the only constant was change. This new, shiny, bustling city was a this is without a this has been, and so, for Nadar, it existed no longer… (Rice, p. 178)

Nadar wrote in an essay ‘Le Dessus et le dessous de Paris’ that was published in Paris-Guide in 1867: “It is no longer Paris, my Paris that I know, where I was born. … I no longer know how to find myself in that which surrounds me.”

Text © Katriina Etholén

As I don’t have any first hand sources, I used Shelley Rice’s book Parisian Views from 1997 as my main source for this story. This was also a good time to go back to this book.

Sources:

Shelley Rice: Parisian Views. The MIT Press, 1997.

Christopher Prendergast: Paris and the Nineteenth Century. Blackwell, 1995 (1992).

David P. Jordan: Transforming Paris. The Life and Labors of Baron Haussmann. The Free Press, 1995.

‘Innovation’ in The Nadars, a photographic legend website. (From BnF Exhibitions. The virtual galleries of the Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Links:

Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s website of The Nadars. I do recommend this website.

You might also like this: A Three-Day Expedition To Walk Across Paris Entirely Underground. This story is an excerpt from Will Hunt’s book that I bought after reading this article. I will write about this book later.

I also found two articles about a book about Nadar, The absurd life of Félix Nadar. (Another book I need to find and read.) The articles can be found here and here.

The cover image shows Nadar’s signature. Source

Dear Katriina

A good follow on from Crossness. Would the lighting underground have been by acetylene?

This is amazing work.

Many thanks

Bob

LikeLiked by 1 person

I gave the link in the article, but in the case you missed it, here it’s again: http://expositions.bnf.fr/les-nadar/en/innovation.html#electric-light

LikeLike

Oh, and thanks for the nice comment!

LikeLike

A very interesting article – I knew of Nadar’s portrait photography and have heard about the balloons, but didn’t realise he’d photographed underground. An 18 minute exposure is impressive although the films (or emulsions) in use in this era were incredibly slow, probably single digits in modern day ISO equivalents.

LikeLike

I knew of Nadar’s underground photography and was aware of him shooting from the balloon, but I was not familiar with the portrait photography. Of course I had seen some of his photos (Sarah Bernhardt at least), but being me, I became familiar with Nadar through his underground stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person